Network Organization

A network’s re-usability lives and dies in its organization and structuring. While there are limits to a modular approach, it’s well worth considering the larger implications around cultivating a forward focused temperament when building new systems. Every project will eventually come up against deadlines, changes orders, and the necessities of project delivery. To the best of our abilities, however, we might consider a tempered approach to thinking about how a particular element might be able to be used and re-used in future projects.

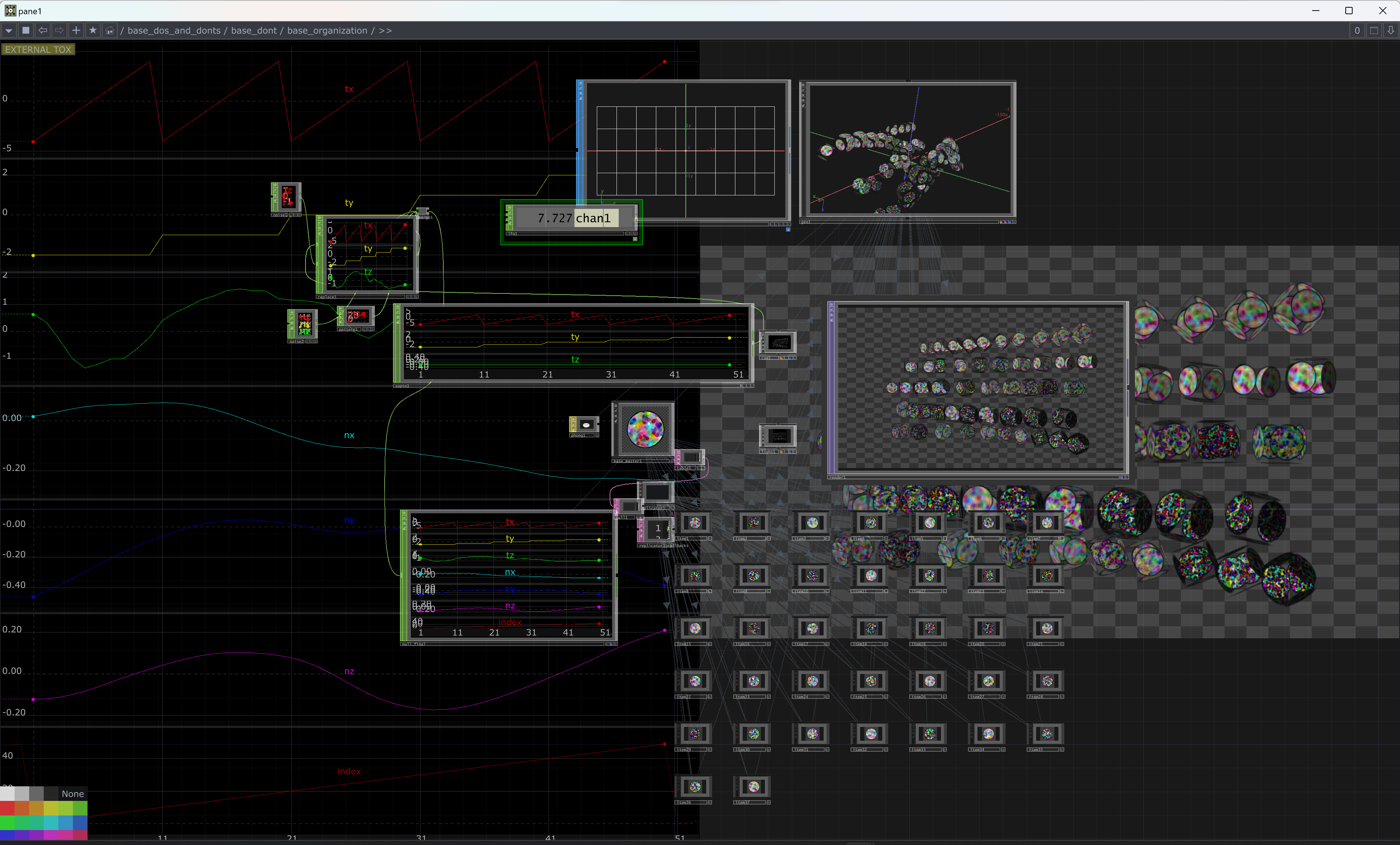

To that end, clear organization and careful planning help facilitate this process. For the sake of a simple case study, let’s for a moment consider instancing networks. For the uninitiated, instancing allows you to reuse a single piece of geometry once it’s been passed to the GPU. This method of drawing geometry is significantly cheaper, computationally, than drawing additional copies of the geometry on the CPU. In principle, you only draw the geometry once, then create a transformation matrix for subsequent copies of the original geometry. The transformation of the copies is most efficiently done in CHOP channels, sometimes initially fed by a geometry converted to channel data.

If we develop the transformation channels in the same network as the rendering system, we’re able to quickly see what’s happening in the process. This also allows for less complicated paths, in a network that is generally flatter. The trade off here is re-usability. This approach typically makes it more difficult to identify how to break apart a network for re-use. The alternative, would be to build the rendering engine as a separate directory from the networking focused on object transformation. It’s difficult to say which is the “better” choice, as both have their merits. Rather, it’s important to understand that one approach has a shorter potential shelf life.

This brings us to a larger question of organization – in what manner should one organize their network. While there aren’t any hard and fast rules, it’s worth considering how you might construct a network as specific to it’s given role. In the example above, you might build a network that was focused on transformational information, while another was focused on texture’s, and finally a network that was the rendering engine. This modular division creates more layers, but also allows for the reuse of any one of those elements – save just the texture building system, or the instances. This also creates space to consider how you might externalize those elements – in this respect a git history would allow the programmer to trace back through various iterations of one element while still preserving the current developments of another – keep all of your advances in texture building, but go back to an earlier transformation system – for example.

If you’re not yet sold on this idea, at the very least consider dividing up your network, spatially, into regions responsible for a given task. Create territories for rendering, texture building, and instance translation. The most difficult to parse networks a wandering collision of every element in a single space. When possible, it is essential that you avoid this kind of programming. All of us invariably work fast and hard, creating functional but not elegant code – that, however, should not be our primary modus operandi.

- Break apart your networks into modular pieces when possible

- Create easily visually navigable networks.

- Avoid mixtures of sizes, distributions, and complex nodal arraignments\

- Think ahead – what organizational method best sets you up for success in the future?

- Limit the complexity of any given network – if you find a network is growing to be too sprawling, how might you re-organize or compartmentalize your implementation?

- Think of your work in terms of a test against the other members of the team – would this structure and approach pass a Barry test? a Vlad test? a Bryant test?

- Make messes you never attend to – “I’ll clean it up later” is the mantra of every creative coder at one point or another. If you have have enough time to have that thought, you have enough time to make a plan to refactor your code for a cleaner implementation.

- Be happy with your first draft – you built it fast and hard on the first pass to rough out the idea, but that shouldn’t be good enough for the final implementation.

- Forget to ask for another set of eyes

- Forget to learn from your mistakes – we all make them, it’s the joy of working on projects at large scales. It’s okay to fall down, just remember to get up and avoid that same trap the next time around.

- Forget that you might not be the person to implement your code – we sometimes have to hand off a project to another team member, or are only in charge of developing a small piece of a larger project. There’s a good chance that what you make will need to be decipherable by another team member. Don’t assume that you will always be available to describe what’s in your network – write it (and document it) so that another could pick it up, and continue with minimal effort.

- Forget to ask for help – we have one of the most remarkable TouchDesigner teams in the world – perhaps the most remarkable collection of them. There’s a good chance that the answers are in the room.